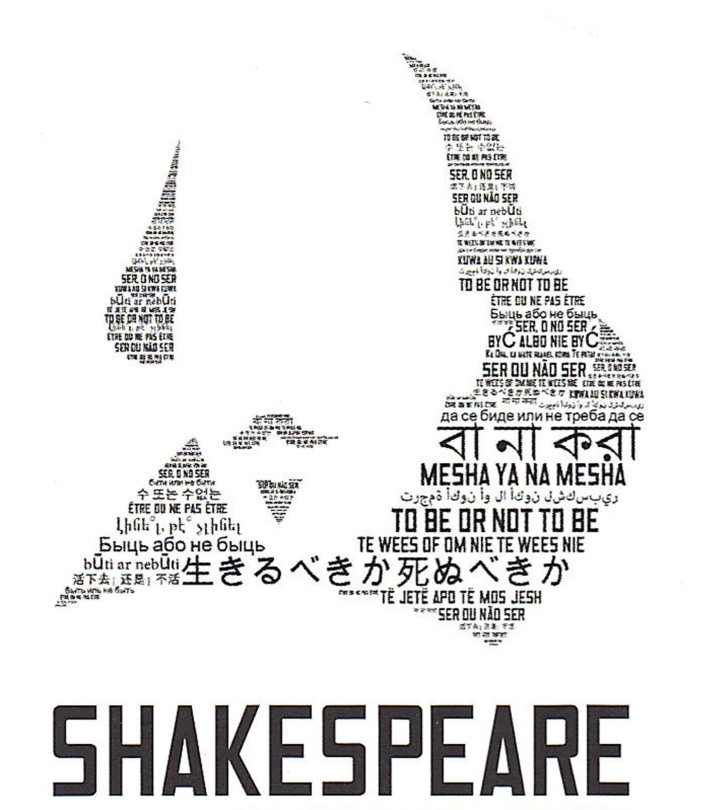

Designed by Graphic Designer Amal Ezzat, Publishing Department, Bibliotheca Alexandrina.

Although[1] he never left England, Shakespeare’s plays are set around the globe which makes him the world’s most famous playwright. In the four centuries since he died, Shakespeare has been translated into more languages than any other writer, from Arabic to Zulu, and has become the most performed, translated and adapted playwright on the planet. The translation of Shakespeare from English into Arabic goes back to the end of the 19thcentury when al-Nahḍa Movement[2] emerged in Egypt promoting an extensive range of intellectual and cultural activities in different aspects including literature, art, language, the media, etc. Shakespeare translations and adaptations have been a pivot of the modern Arab theatre in response to a global medley of international sources and models, not only British texts but also French plays, Italian operas, and American productions.

In response to that cultural revival in education and thought, translation emerged as an intellectual and literary trend, marking the beginning of a new era in the Arab world; where scholars and intellectual institutions started to show an unwavering interest in the ‘transfer’ of all forms of knowledge and art from Europe. To that end, leading thinkers and institutions launched and encouraged different means of communication with Europe, such as cultural exchange and study trips as well as translating the works of remarkable European literary figures and scholars into Arabic to acquaint Arab peoples with the cultural heritage of modern Europe, and bring them closer to what was happening overseas when Europe had reached the height of its enlightenment. Given the prominence of Shakespeare all over Europe at that time, he was one of the first figures to be translated and introduced to the Arab readers, which is quite interesting from a historical point of view since this makes him a key figure in the renaissance of two cultures with a gap of four hundred years approximately separating between Shakespeare’s first appearance on the English, Elizabethan stage and his rebirth in the Arab arena. In other words, the translation of Shakespeare into Arabic marks a turning point in the history of Arabic language, literature, and culture, not only because he was the first English dramatist to be presented on the Arab stage, he was also the only English playwright to be widely translated in the late 19th century.

The translation of Shakespeare from English into Arabic went through a long journey of development passing through three main phases: adaptation[3], Arabization[4], and finally translation, in the strict sense. The first attempts at translating Shakespeare into Arabic were done for the stage. Those early attempts of translation took the form of mere adaptations of the original texts, which were appropriated to the taste and culture of the audience. To bring the Shakespearean texts closer to the Arab audience, translators dealt with them flexibly introducing various changes to their main components and features including the plot, setting, characterization, etc. Hamlet, Othello, and Macbeth are among the Shakespearean plays that were mostly adapted to the tradition of the Arab theatre, and there were even translations that tended to drop whole scenes in the play, alter the entire ending, and use the local Egyptian dialect.

In the century since then, a vast variety of directors and adapters in Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Jordan, Morocco, Tunisia, Palestine and other Arab countries have produced versions of Shakespeare’s plays to speak to their own and audiences and circumstances. The first Arab encounter with Shakespeare was through the Egyptian stage, where Syrian-Lebanese immigrants, many knowing little English, retooled French translations of the plays to please Cairo’s emerging middle class. Najib al-Haddad (1867-99) adapted Romeo and Juliet around 1892 as a melodrama that depicts a demonstration of the dangers of blood feuds and arranged marriages. TanyusʻAbdu’s (1869-1926) adaptation of Hamlet was based on the French adaptation by Alexandre Dumas, and unlike its source, it ended happily. Othello has been adapted as a prooftext about Orientalism or a tragedy about gender violence.

This made Shakespeare gain great popularity in the Arab world because he was contemporarized by being translated, staged and adapted to the local taste and colour of the area. Most Shakespeare-based works are in standard Arabic, the formal language used by intellectuals for literary and media writing throughout the Arab world. Yet some Shakespeare adaptations are in colloquial Arabic. For example, Richard II was performed in Palestinian Arabic by Ashtar Theatre, a dynamic Palestinian theatre company with a global perspective, who brought their direct storytelling style to Shakespeare’s great masterpiece.

At the beginning of the 20th Century, more serious translations of Shakespeare started to appear in response to the criticism of adaptation which was considered a distortion of the Shakespearean text. This encouraged leading men of literature to produce much more reliable translations of the Bard keeping the structure, plot, and characterization intact and limiting their changes to the linguistic content of the play by omitting some sentences or scenes or rephrasing certain linguistic structures without affecting the course of events or the core of the play. This was referred to later as ‘Arabization’. For people like Ahmad Shawqi and Khalil Muṭran, who both played a leading role in bringing up the notion of ‘Arabization’ to the translation of Shakespeare’s texts, the main focus of their translations was the thematic content of the text without being bound by the linguistic formalities of Source Language structures. They wanted to ‘arabize’ the metaphorical language of Shakespeare to make it comprehensible and natural to Arabic language readers; therefore, they were tempted to make shifts that went as far as deleting and/or adding sentences and paragraphs in the original text to make it more appealing to Arab readers.

In the middle of the 20thcentury, the translation of Shakespeare’s plays into Arabic entered a third stage where Shakespeare’s plays started to appear in different Arab countries in new translations sponsored by the Cultural Committee of the Arab League which was founded for the sole purpose of translating the masterpieces of world literature into Arabic. Eminent literary figures and translators in the Arab world were appointed to translate all of Shakespeare’s work. Jabra Ibrahim Jabra was the first translator to produce the first authoritative translations of Shakespeare, setting the foundation for translation as an accurate re-production of the original text. To a great extent, the translations that started to appear as of the second half of 20th century were considered faithful to the original because they were committed to translating it as closely as possible without changing anything in its structure, plot, characterization, sequence of events, or linguistic content.

Prior to the launch of the Arab League’s initiative to institutionalize the translation of Shakespeare on the professional level, the translation of Shakespeare into Arabic had reached a mature phase. With translators becoming more dedicated to the accurate representation of Shakespeare’s language in Arabic, a new literary movement began to be involved in improving and refining the translation of Shakespeare. This trend aimed at examining the translations of Shakespeare to evaluate their contribution and check how far they match the original texts in form and content. Hence, the interest in Shakespeare no longer remained limited to the themes of his plays and the meaning beyond his words. Shakespeare’s language itself became the main criterion for testing the translator’s competence in bringing the Shakespeare’s art to the Arab world. This gave rise to academic and literary critical studies that meant to improve the translation of Shakespeare and producing better Arabic versions of Shakespeare for Arab readers and to highlight all the major problems which confront translators in translating Shakespeare into Arabic.

The idea that Shakespeare is a global author has taken many forms since the building of the Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre[5] in London. Launched by the Globe theatre, the Global Shakespeares Video & Performance Archive[6] provides all productions, translations, adaptations, spin-offs, and parodies as well as Arab-themed Shakespeare works in the world. The project honors the diversity of the world-wide reception and production of Shakespeare’s plays in ways that nourishes the remarkable array of new forms of cultural exchange that the digital age has made possible. It also provides global, regional, and national portals to Shakespeare productions within a federated structure in order to promote cross-cultural understanding and serve as a core resource for students, teachers, and researchers from all over the world.

Being a global author, Shakespeare has been translated into more languages than any other writer, which makes him the most performed, translated and adapted playwright on the planet. Since al-Nahda movement until present, the translation of Shakespeare went through three main phases: adaptation, Arabization, and finally translation. Shakespeare translations and adaptations have been a staple of the modern Arab theatre in response to a global medley of international sources and models. Given that most Shakespeare-based works are in standard Arabic, some Shakespeare adaptations are in colloquial Arabic to make it more appealing to Arab readers. Thus, it is more accurate to refer to Shakespeare’s appropriation into Arabic literature and theatre as “Arab” rather than “Arabic” Shakespeare.

[1] This article was published in The Bibliotheca Alexandrina Newsletter (Quarterly Issue No. 17, October 2014). It is mostly inspired by a keynote speech on Shakespeare and Translation by Patrick Spottiswoode, Shakespeare’s Globe Education Director, delivered at “The Literary Translation Summit” in Doha, Qatar. It washeld on the fringe lines of the Doha Book Fair during 8-12 December 2013, under the auspices of The British Council, Bloomsbury Qatar Foundation Publishing and the British Centre for Literary Translation.

[2]Al-Nahḍa is the Arabic for ‘renaissance’; a movement of intellectual reform considered to be the Arabs’ counterpart of EuropeanEnlightenment.This cultural revival began in the late 19thcentury in Egypt, then moved to other Arab countries.

[3] Literary adaptation is the adapting of a literary source (e.g. a novel, short story, poem) to another genre or medium, such as a film, a stage play, or even a video game.

[4] Arabization describes a growing cultural influence on a non-Arab area that gradually changes into one that speaks Arabic and/or incorporates Arab culture and Arab identity.

[5] Founded by the pioneering American actor and director Sam Wanamaker, Shakespeare’s Globe is a unique international resource dedicated to the exploration of Shakespeare’s work and the playhouse for which he wrote, through the connected means of performance and education. (Shakespeare’s Globe Official Website: http://www.shakespearesglobe.com/about-us)

[6] Global Shakespeares Video & Performance Archive is a collaborative project providing online access to international performances of Shakespeare from many parts of the world in many living languages as well as essays and metadata provided by scholars and educators in the field that change how Shakespeare’s plays are perceived. (MIT Global Shakespeares Video & Performance Archive-Open Access Website: http://globalshakespeares.mit.edu/#)

Link to the article in the BA Newsletter: BA Newsletter Issue No. 17 (Oct. 2014)

©2018 Dina Al-Mahdy All Rights Reserved

thanks for this article. Wonderful to know how the translation and performance of Shakespeare hsa spread around the globe.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad that you like it Jean. Thanks for your valuable feedback 🙏🏻

LikeLike

[…] the twentieth century[1], language boundaries persist in creating a barrier to broaden distribution of content and […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

wow how fascinating, I had no idea Shakespeare was that universal .. impressive!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you find this article interesting, Kate.. I love to hear your feedback. Always 😍

LikeLiked by 1 person

thanks Dina 🙂

LikeLike

أحسنتي

LikeLiked by 1 person

اشكرك يا سو ❤️😍

LikeLike