Dina Al-Mahdy, Saturday 13 Dec 2025

Dina Al-Mahdy explores the digital transformation taking place in reading today and the emergence of hybrid reading habits among young people.

Reading has long been a quiet and peaceful act that takes place in parks, on trains, and by bedside lamps. It is an intimate conversation between the reader and the book.

However, that dialogue is radically shifting today. A new kind of literacy has emerged in recent years in the form of reading that can listen, engage, adapt, and even anticipate. In addition to serving as paperless alternatives, audiobooks, e-books, and digital storytelling are actively changing the way stories are created, presented, and experienced. They are also shaping the habits and imaginations of young readers worldwide, including in Egypt.

This new dialogue between reader and text and the rapid expansion of electronic and audio books have raised concerns about the prospects of reading among young people, however, as well as strategic changes and grave concerns besetting publishers and authors regarding artificial intelligence (AI) that is seen as both a catalyst and a controversy in the publishing and creative domains.

For hundreds of years, the printed page set the pace and content of reading. Reading used to be a quiet ritual that was made more personal by the book’s physical presence. This ritual had a visible rhythm: the smell of ink, the sound of pages turning, the slow ending of a chapter, and the weight of a volume.

People owned, borrowed, and showed off books on their library shelves. However, all this started to fade with the rise of the Internet, cell phones, and fast connections. In the era of smartphones, streaming, and AI, the physicality of reading is evolving right before our eyes and is now reimagined, fluid, and borderless.

Reading is evolving into a digital ecosystem that affects not just how we read stories but also how we learn, remember, and think. The book is no longer on the shelf; it is now in our ears, on our screens, and even in the algorithms of social media.

This covers everything from interactive narratives to AI-narrated stories, audiobooks, and e-books. The way young people in Egypt and the Arab world use language, culture, and their imaginations is rapidly changing as a result. The printed book no longer has a monopoly on reading. A new type of literacy that engages with multiple senses, learns, and listens is emerging.

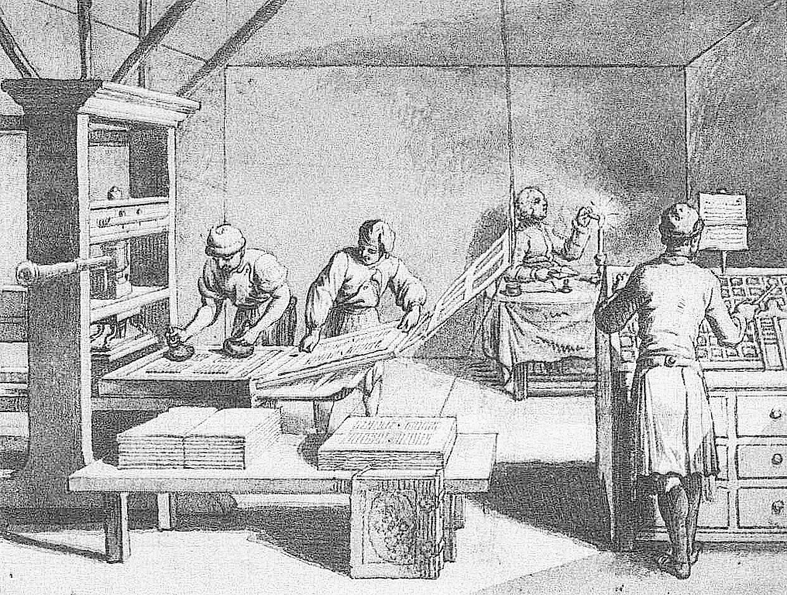

By making knowledge more widely accessible, the digital transformation of reading is bringing about a revolution akin to that of the printing press. The first step was e-books, which were simple to read anywhere. Finding books quickly was made simple by digital libraries and subscription services, and audio transformed reading from a visual activity into a multisensory one.

The real change was the rise of audiobooks, however. At first, being able to “read” while driving, working out, or cooking was just a convenience. Now, it’s a new way to experience stories through sound. Audiobooks and digital platforms have gone from being niche to mainstream thanks to software businesses turning listening into subscription ecosystems that encompass music, podcasts, and audiobooks. Millions of readers throughout the world now listen to books instead of reading them in print.

Thanks to streaming and smart devices, the billion-dollar global audiobook market is still growing quickly. Paper continues to be used as a ritual and an artefact, so this is not the end of printed books, but it does represent a significant change in the way that stories are shared and attention is structured.

Young readers are using mobile apps and e-libraries for quick access to literature, sometimes consuming more stories in a month than their parents did in a year. Several Egyptian publishers have started releasing Arabic audiobooks via digital platforms.

AUDIOBOOK REVOLUTION: Being told a story has a deeply human quality, notably because voice existed before writing. As a result, audiobooks have brought the earliest storytelling medium back to life. A narrator’s voice becomes a performance that can change tone, pace, and emotional shading, providing an intimacy that goes beyond simple convenience.

Audiobooks also level the playing field. Listening facilitates inclusion for individuals with visual impairments, reading difficulties, or busy schedules. Narration helps language learners understand what they hear. For the multitasking younger generation, it lets literature flow naturally into everyday life. Examples of how technology has transformed audiobooks from specialised formats to mass-market goods include smartphones, smart speakers, and subscription bundling. Platforms are investing large sums of money in production.

But the shift to audio raises difficult problems, particularly about narration and technology’s growing role. “Younger readers today switch between formats without thinking about it, picking the one that is quickest, easiest, and cheapest. The new generation loves digital reading because it gives them instant access and costs less. Audiobooks and interactive formats also open doors for people who may not be interested in traditional print,” said Noura Rashad, a director at publisher Al-Dar Al-Masriah Al-Lubnaniah in Cairo.

Artificial intelligence has also become a disruptive force as well as a revolutionary tool in the publishing industry. Prominent audiobook platforms have experimented with AI-generated voices or synthetic narrators that can read complete novels in human-like tones for a fraction of the cost. And while publishers benefit from this technology, writers and narrators worry about their future.

Voice performers want stricter consent and compensation laws, and the issue is growing worldwide. Nowadays, ethical publishing increasingly entails asking not just what is produced but also how and by whom. The risk is even higher in Egypt, where literary tradition carries linguistic and cultural nuances. Machine narration can mispronounce Arabic words, flatten dialects, and overlook complex emotional tones that characterise the richness of the language. The human voice, with its accent and cadence, is still indispensable, many feel.

Bookstores and libraries are also changing. They used to symbolise community, and digital libraries may be their contemporary counterpart. Libraries are changing from being symbols of print to becoming hybrid organisations. E-lending, digital archives, and remote access have allowed libraries to reach a wider audience outside of their physical walls. National e-libraries and digitisation initiatives have made it possible to find and share rare and local materials in ways that were previously impossible.

The Bibliotheca Alexandrina in Alexandria has long been the pioneer of this change. It has embraced digital transformation with its large e-library, digitisation projects, and online databases, and it is seen as a model for bringing knowledge back to life. Its Digital Assets Repository (DAR) stores all kinds of media and makes more than 210,000 books available to the public online. This helps connect resources with learners.

Digital storytelling is another change in reading that is like an archipelago because it includes interactive fiction, hypertext stories, game stories, serialised micro-chapters for social media, and transmedia worlds. A book that is printed is a solid island of words, but young people who grew up in places where they could get feedback right away often like stories that respond to them.

On platforms like Wattpad, Hooked, or their Arabic equivalents, writers can turn their stories into experiences by adding multimedia elements, responding to reader comments, and serialising their fiction. Young audiences today are not just reading stories; they’re also writing them.

This culture of participation is even stronger because of social media. BookTok and Instagram literary communities are bringing reading back into style. Young people talk about stories, share quotes, and recommend books in short videos that millions can view.

This is a return to the social side of reading, but this time it’s done through screens and hashtags instead of cafés and salons. It requires readers to learn new skills, such as how to navigate, how to use the new media, and how to be critical of algorithms. Schools and libraries must change their curricula to help students develop these skills.

READING IN A HYBRID AGE: Younger people do not only read one type of book. They do not just stop reading print and switch to digital; instead, they make reading spaces that mix print, screens, and audio depending on how they feel, what they are doing, and the situation.

Surveys show that reading on a screen is not the same as reading on paper. Reading on a screen is quick and easy, while reading on paper is deep and focused. A teen might also listen to a fantasy book on their phone while making fan art based on it and then talk about it in an online forum.

In Egypt, mixed literacy is rapidly expanding. Young people can switch between formats with ease. For instance, they might participate in an online author Q&A one day after attending an in-person reading session. They may listen to an author’s book in Arabic, watch a brief documentary about them, and then share a quote on social media.

This is reading in motion, but it is still reading. However, access is still uneven. Affordable local language content is a problem because socioeconomic inequality and regional connectivity pose serious challenges.

However, Ahmed Salama, publishing manager at the Dawen Publishing House, believes that this means that reading now fits better with the fast pace of modern life.

“Audio and electronic books are a new opportunity to reach readers and let them easily access thousands of titles right away. This is especially true in places where it’s hard to find a bookstore. This is a great chance to get more people to read, and it will also be good for print readership. No matter when or where, a reader is a reader. Audiobooks have also made it possible to read during times that used to be ‘dead time’ for reading, or times when reading was not an option. You can listen to books while you drive, work out, or do chores around the house that do not require a lot of focus,” he commented.

Reading is of course a mental activity, and research indicates that reading style has an impact. People who read online may skim more, multitask more, and retain less information when they navigate between hyperlinked texts. Many people still find it easier to read deeply on paper. To read on a screen, we need to learn new skills like paying close attention, ignoring distractions, and determining whether a piece of news is true.

“What I do see as a challenge is the tendency towards the rapid consumption of digital content, which may threaten the reader’s ability to engage with long-form texts that require sustained focus and effort,” Salama said.

This could undermine the growth of critical thinking abilities and subtly alter the reader’s perception of the worth, sanctity, and significance of the reading process. Furthermore, it is now feasible to produce books in numbers that do not always correspond with quality. Readers, particularly younger ones, may find it difficult to distinguish between excellent and unique content and inferior work.

However, for Alexandra Kinias, author and founder of the Women of Egypt Network, all formats, “e-platforms, audiobooks, and paper books are welcome. What I read depends on my time and accessibility. I can’t take many books around with me, but I can read online as a library member while exercising, walking, or doing other activities.”

Kinias said that the younger generations’ use of e-books and audiobooks is welcome. Books have endured for millennia. People shifting to other platforms doesn’t mean books are useless. Physical books may become historical relics like videotapes or cassettes, but we should just adjust and accept these changes, she said.

AI is also now a part of almost every modern reading ecosystem, from writing and editing to translating and recommending books. Generative tools are useful for writers, and AI-assisted translation can translate works from one language to another in just a few seconds. Some Egyptian publishers are trying out AI for editing and cataloging, but they are doing so carefully.

AI can be both a source of inspiration and a danger to writers, some say. People are worried that relying too much on AI could stifle creativity, even though it can also come up with new ideas. The industry’s rush to use AI-generated voices has raised concerns about job losses, consent, and intellectual property. The moral choices made today about fair pay, openness, and cultural differences will have an effect on the creative economy for many years to come.

“More and more people are using AI for editing, translation, and even narration, which is making things better than ever before. AI will definitely change how we work, allowing publishers to work faster and smarter. However, it can’t replace the human touch that goes into telling a story. The meaning of a book comes from how emotionally smart, culturally aware, and creatively intuitive it is,” said Rashad.

“The future lies in letting AI improve our work while making sure that the heart of publishing stays clearly human.”

PUBLISHERS AT A CROSSROADS: Publishers are under pressure to both monetise content and carry out their cultural missions of preserving and promoting local literature in a market that is becoming more and more subscription-based.

The digital transformation presents both opportunities and challenges for Egyptian publishers. On-demand, streaming, and subscription business models are displacing traditional ones. “As publishers, we have an important concern: that the increasing dependence on screens may weaken the quiet, immersive relationship readers have with printed books,” Rashad said.

Some local publishers are investing in audio studios to maintain creative control, while others are collaborating with global platforms like Storytel or Google Play Books to expand their Arabic catalogues. The financial equation is complicated because creating a professional audiobook necessitates a large investment in editors, sound engineers, and voice actors, resources that independent houses usually lack.

“Many readers worldwide feel overwhelmed by constant digital exposure, which has led to a renewed appreciation for physical books and the focus they provide. This reinforces our belief that reading won’t be solely digital in the future. Instead, it will be a hybrid setting where digital formats improve accessibility while printed books continue to offer a unique emotional and intellectual space,” Rashad added, saying that she believes it is our duty to maintain this balance and ensure that the physical book remains an important part of the lives of younger readers.

Salama believes that the creative sector has a great opportunity to highlight the human touch and everything that is essentially human, aspects that distinguish it from AI. “I continue to view AI as a kind of cutting-edge technology that will undoubtedly assist with some operational tasks that support the creative process. It won’t, however, replace true creativity,” he said.

“Books were once copied entirely by hand, sometimes by the authors themselves, prior to the invention of printing machines. Is it reasonable to believe that the advent of printing and then digital reproduction negatively impacted the creative process?”

One of the biggest shifts in reading that we are currently witnessing is the shift from paper to pixels, from libraries to clouds, and from the printed word to the digital screen. But the core characteristics of reading, namely curiosity, empathy, and reflection, remain unchanged. Our task is to guide change in a sensible manner rather than to resist it.

People may think of AI as a tool that makes them more productive, but it is not a substitute for creativity. It could help creativity grow, come back to life, and reach new heights. But it doesn’t replace it. “In the end,” Salama said, “the things that need to stay deeply human will stay deeply human.”

The future of reading will be influenced by legal, artistic, and institutional decisions about who controls narratives, who gets paid, and who gets to listen, in addition to technology and markets. The opportunity and responsibility to steer that future in the direction of access and plurality rests with Egypt’s cultural sector, which includes its publishers, writers, and libraries.

To ensure that digital innovations benefit culture rather than just commerce, a multifaceted approach is required. All creative labour must be fairly compensated; cultural investment in Arabic-language content must be given top priority; public infrastructure must be funded to maintain fair access and archiving; and readers must be informed when AI has been used.

- A version of this article appears in print in the 11 December, 2025 edition of Al-Ahram Weekly

To read the full article: https://english.ahram.org.eg/News/558367.aspx